The situation of the children in Fukushima was only brought to the general awareness in a marginal way and with delay. It was on 19 April 2011, a whole 40 days after the reactor accident, that the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) published the first guidelines for children's outdoor activities. Should radiation levels exceed 3.8 microsieverts per hour, children were only allowed to spend one hour outdoors each day. As this limit was far above the average natural radiation exposure (e.g. 0.08 microsieverts per hour in Tokyo and 0.43 microsieverts per hour in Austria), the city of Koriyama was one of the first municipalities in Fukushima Prefecture to lay down its own measures: the municipal education office called on all schools to refrain from outdoor activities in April 2011 and began removing topsoil from schoolyards and playgrounds. As early as May, the MEXT lifted restrictions on all outdoor activities, as radiation levels had dropped to some extent. This created outright resistance among the population. In Koriyama, children aged 0 to 2 years were still restricted to 15 minutes outdoors per day, children aged 3 to 5 years to 30 minutes. At the beginning of the school year in April 2012, Koriyama City lifted the restrictions on outdoor activities as well, mainly because, as a result of decontamination and natural attenuation, radiation levels in schoolyards averaged 0.2 microsieverts per hour. However, precautions for outdoor play still required children to wear long trousers, long sleeves and a hat. Walking on grass was prohibited, as well as touching soil, sand, puddles or pond water. Putting their hands in their mouths was also forbidden, and children were encouraged to always wash their hands and gargle after playing. The impact of restricting children’s outdoor activities in Fukushima was reflected in the deterioration of their physical and motor skills such as gripping strength, running and throwing balls. Many activities were moved indoors, which meant that nature after nature had lost its former validity.

In her installation, Hana Usui references the situation of the children at that time in particular, as well as the consequences of the nuclear accident in general, which, although it occurred over a decade ago, has driven the discussion about a worldwide phase-out of nuclear power. After the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and considering Japan's seismically active geography, it is surprising that the Land of the Rising Sun, pressured by the USA, has embraced the path of nuclear power for civilian use. The wound that the nuclear disaster in Fukushima has left on the country and its population is therefore all the more drastic. As a result, the work of several Japanese artists has become increasingly political. Hana Usui had always been interested in politics, but it was only after the Fukushima incident that she began to dedicate her artistic vocabulary to examining injustices from her home country. She travelled to Fukushima in the wake of the nuclear disaster and photographed and filmed the area: the nuclear power plant itself, the tsunami-ravaged beach and forest, the countless black bags of contaminated soil, a Geiger counter in a schoolyard, contaminated cows left alive, etc. However, when the artist participated in the exhibition ‘No more Fukushimas’ curated by Marcello Farabegoli in 2014, the wound of Fukushima still seemed too fresh to her. She did not want the people who were still suffering there to be offended or insulted by her message. Therefore, she initially dealt with the devastating consequences of the atomic bombings, which tied in more closely with Fukushima than expected. Gradually, she approached the Fukushima issue through other highly charged issues in her country, especially those relating to discrimination. Just as atomic bomb survivors (Hibakusha) had been discriminated against after the Second World War as being contaminated, children from Fukushima were bullied for the same reason. With the Fukushima cycle, Usui has now, in a sense, come full circle.

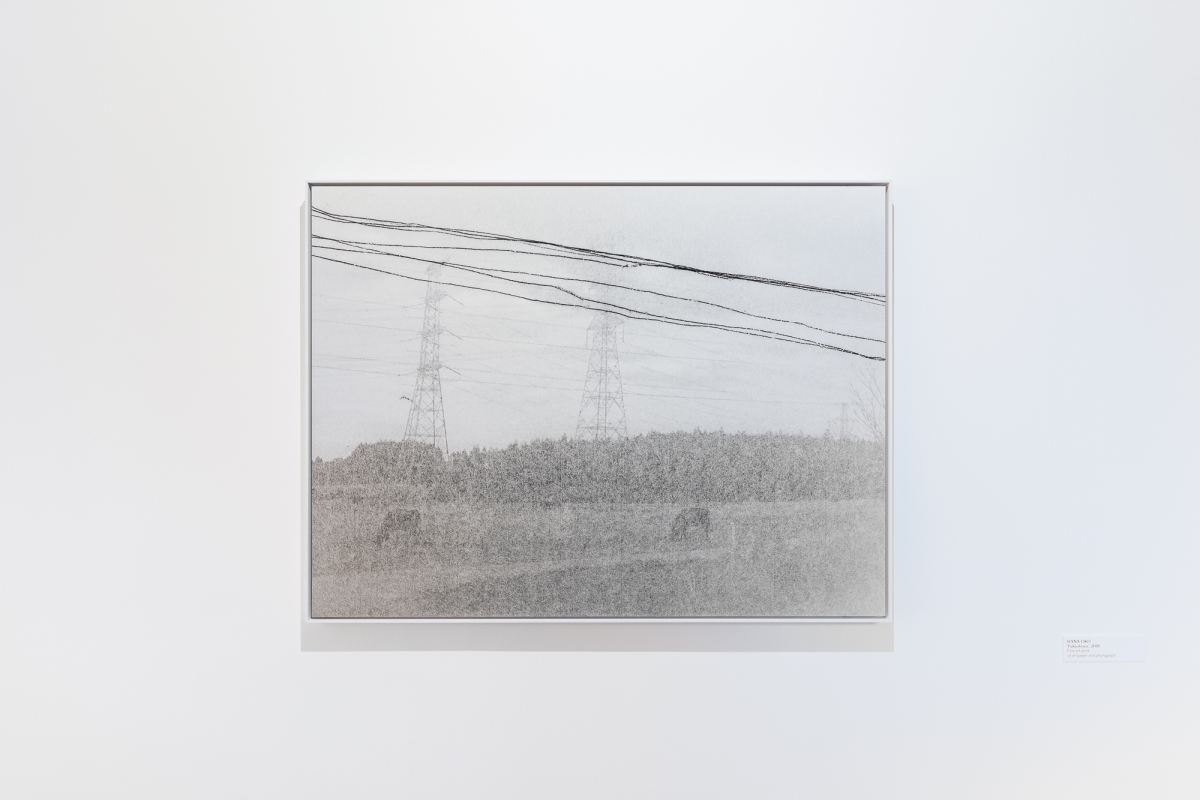

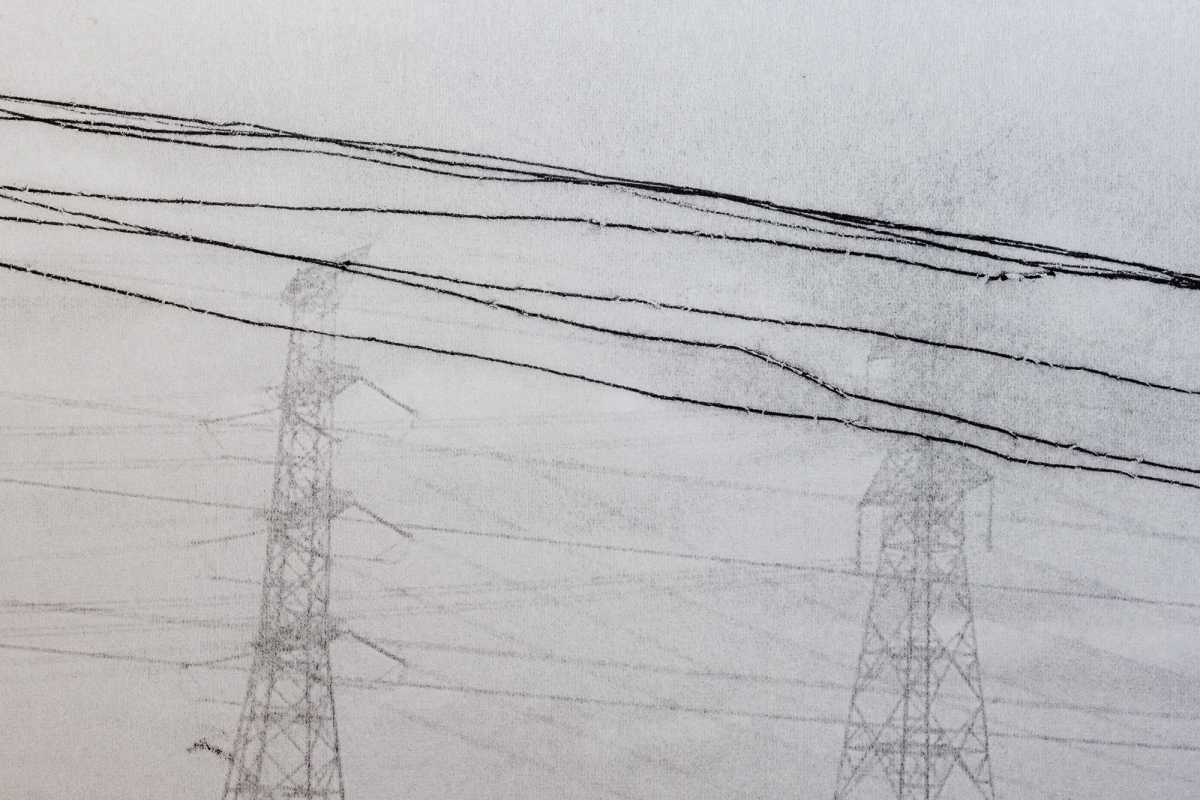

For Usui, the 13-part photo/drawing-series ‘Fukushima’ (2019), marks the beginning of the artistic exploration, through which she examined the issue of how changes in the landscape unfold over the years and affect the mental and cultural memory. She overlaid the black-and-white photographs with semi-transparent paper and covered them with black lines. These shaky lineaments hint at the dense high-voltage electrical network that is spread ominously around the Fukushima reactor. The whole process results from Usui’s drawings, which also contain photographic and cinematic elements. Based on her intensive study of a subject, the artist abstracts one or more essential motifs and draws their movement and development processes as if they were photograms or stills. She transfers the visual components of the cloudlike ink of her earlier works by applying a thin layer of paper over the photographies, whereby the artist tests the validity of the statements made by the photographic dispositive. She employed that same technique first in 2018 in her photo/drawing-series on the death penalty in Japan, titled ‘Tokyo Koshisho’. Although condensed into concrete images, in Usui’s photographic views the actual motifs of the depicted surroundings are only recognisable to a small degree. Thereby the artist addresses Japan’s relationship with negatively charged phenomena, which politicians refuse to admit and therefore try to visually ban from the public space. The artistic investigation of such endeavours not infrequently leads to forms of censorship. With her special technique the artist anticipates potential censorship models and while doing so attempts to artistically articulate the essence of Japanese thought.

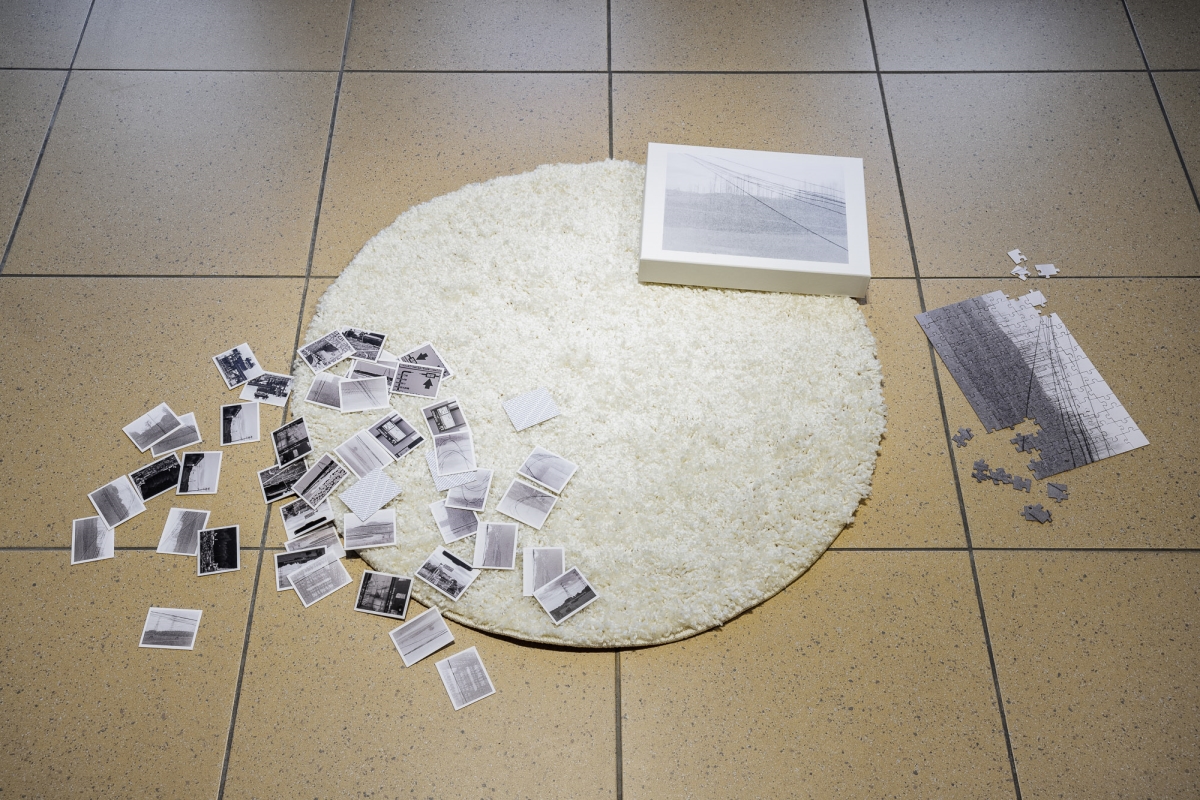

In her current installation at Neuer Kunstverein Wien, Usui integrates the motifs of her Fukushima series into the setting of a children's playground, set up indoors, as contact with soil, sand and water outdoors was not recommended for children. Usui designed several puzzles as well as memory cards on which her photo/drawings can be seen, which have been distributed on children's play table with matching armchairs as well as on the surrounding floor. The theme is in no way a positive one but is intended as a kind of memorial in the room to remind us of the real catastrophe that caused radiation damage to people, animals, and nature. Usui also created the installation ‘Fukushima - 10 Years Later’ on the occasion of the ten-year commemoration of the reactor accident on 11 March 2021 in the Red-Carpet Showroom on Karlsplatz in Vienna. Placed inside a showcase in the underground station, she took one of her photo/drawing-works as a starting point or background element, around which the artist created a display of fishing nets, animal and grain parts, and what appeared to be shells, washed-up in ash and sand. Due to the radioactive contamination, the population - including many farmers and fishermen - had to leave the restricted area (‘kitaku konnan kuiki’, literally: difficult-to-return-home-to area) around the reactor. The breeding animals, which were also abandoned, went wild, starved to death or had to be culled later. The entire farmland as well as the abandoned houses became overgrown with wild plants. Fishermen were either not allowed to fish in the area or had to throw away countless radioactively contaminated fish, over and over again. To capture all this misery, and at the same time the decadent aesthetic of decay and renewal, Usui continued this theme more extensively at Vienna Art Week in the exhibition ‘House of Losing Control’ in November 2021. This time, there were two abandoned rooms, a changing room with overturned office chairs and lockers that looked as if it had to be abandoned in a rush, and a second, former washroom where fishing nets were strewn about exuberantly. Here, too, animal and grain parts as well as shells were used as set pieces. An old television monitor played a poetical-documentary video about the area and situation around Fukushima, which Usui had worked on together with ORF journalist and Japan expert Judith Brandner.

The above-mentioned video (‘Fukushima’, 2021) was shown for the first time at the Berlin Art Week 2021 and will be shown again at Neuer Kunstverein Wien, where it will be projected in a separate room in order to point out, among other things, the false truths that are being spread to propagate nuclear power. Here, text fragments, which could just as well have come from the EU's green energy statements announced at the beginning of January 2022, have been used ironically: ‘Nuclear power is clean. Nuclear power is sustainable. Nuclear power is good for the environment. Nuclear power is CO2-free. Nuclear power is reliable. Nuclear power is the energy of the future.’ The effects of the disaster in Japan have shown how severe the consequential damages of nuclear power can be. ‘It has been ten years since the dismantling of the nuclear power plant began. It will take another 30 years until all six reactor blocks are disassembled. Four thousand workers are working on this every day. It will take millions of years until the radioactivity from the fuel rods of Fukushima has completely disappeared,’ Brandner says in the video. Also on view in the video are the beach sites that Usui addresses, abandoned, and washed up by the sea, as well as overlays of her works. Sand as an element is made manifest in the installation at Neuer Kunstverein Wien in cream-coloured, circular carpets underpinned by the light-brown exhibition floor. Along the walls there are lines reminiscent of the high-voltage power wires that appear in the photo/drawings and are ever-present in Japan, encircling or enclosing the space. The children have been deprived of the hope of playing on the beach as they once did. Presence and absence are linked in the confrontation with an invisible energy, which determines the relationship between man and nature, and which is being artistically examined by Usui.

Text: Walter Seidl

read less