Vienna, year unknown

‘…but the bodies in the figurehead which they formed looked into the darkness, as one looks into the future’.

Jean Genet

As the result of an amorphous present, the elements in this show may take the shape of things yet to come. The brutal transformation of nature by capitalist societies, the subduing of non-western cultures and wisdoms, as well as the corruption of language and communication by algorithms, sets the political sphere into an entropic maelstrom of destruction and instability. On the verge of a virtual collapse of meaning experimented in our times, faced with a state of imminent aporia, The devil to pay in the backlands enquiries about the future sideways, rearranging visual tropes, and perhaps luring one, as Catherine Malabou expresses, ‘to see (what is) coming’ .

Devised as an occupation, this exhibition shelters a myriad of entities under the dome of what used to be an autohaus, a former temple of consumption and commodity fetishism. Such postmodernist building of sorts, located just outside the city center of Vienna, works as a provisional space, an arena where the body, the architecture, the urban landscape and their topographies engage in a semantic intercourse that explores the limits of plasticity in current times.

The devil to pay in the backlands navigates different narratives, anachronies and archaeologies in an attempt to observe, learn from and share a common ground with diverse creatures, objects and technologies which, in spite of their uncanny features, appear strangely familiar to the senses of those eager to excavate the ulterior layers of reality in order to attribute meaning to unforeseen social-political scenarios and cultural manifestations. History unfolds in the wake of an ‘unequal accumulation of time’ , in the overlapping of material and symbolic culture, artificial and natural matter — and therefore space derives from both the past and the present, allowing for latent futures to acquire shape.

read more‘Doesn’t everyone sell his soul? I tell you, sir: the devil does not exist, there is no devil, yet I sold him my soul. That is what I am afraid of. To whom did I sell it? That is what I am afraid of, my dear sir: we sell our souls, only there is no buyer.’

João Guimarães Rosa

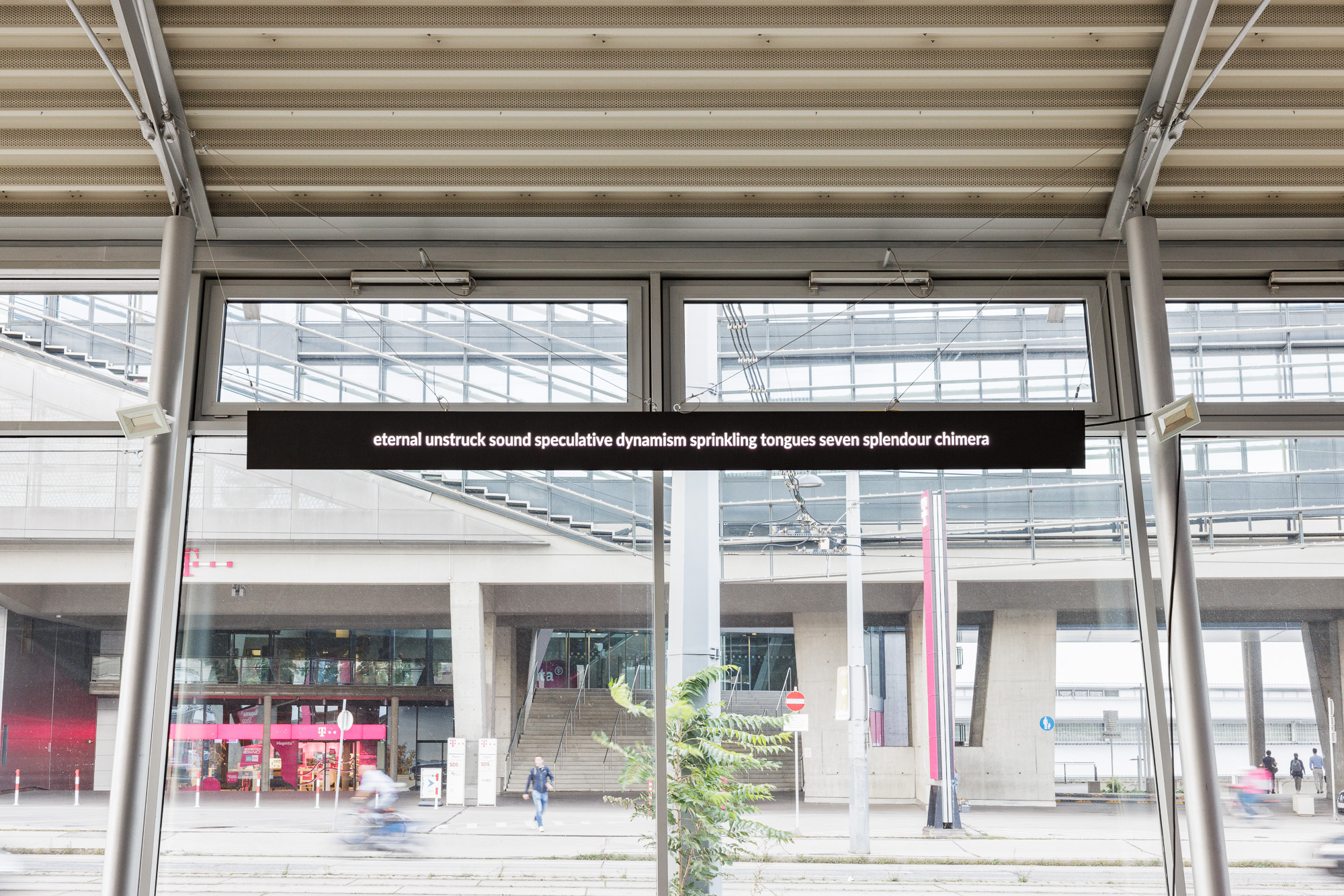

The fear of what is foreign, alien to the Occident’s supposedly sealed landscapes and bodies, pervades the very search for the ‘who of things’ , that hidden nature most blatantly ignored in order to cast a vertical light over human history. And insofar as one might entertain the idea that through destruction the Other will be consumed, devoured, devoid of its most powerful resources, alas!, something else takes place instead: a chimera emerges under a transformative and, at times, blinding light — anthropophagy as a rite and as a political tool. Only partly human, the contingent of entities gathered in this tent exist under the sign of cannibalism and transformation: as if by digesting each other’s bodies, as well as other organic and inorganic matter, machines were turned into sentient beings, debris into oneiric material, vital organs into oracles, vegetables into a liturgic piece of yore.

Borrowed from Guimarães Rosa’s linguistic ground-breaking novel of the same title, The devil to pay in the backlands speaks of precariousness, destruction, regeneration, degeneration — and in a less evident Faustian key, also about a pact with the Devil . In doing so, it flirts with a future landscape, a no man’s land where economic negotiations have come to a close, exhausting nature, politics, affection and language altogether. The promiscuous relationships long stablished with material resources have increasingly deepened the abyss between humans themselves and the natural world in a broad extent; thus, technology emerges as a second nature, forging virtual, albeit ubiquitous, hegemonic political and ideological ties with a vast array of distinct cultures across the globe.

Over this treacherous zone where life risks disappearing, and technology subsumes humankind to a grammatical dynamic of its own accord, lies a world of many worlds — an existential plane in which the extensive totality of things and relations created by human beings appears to take on a life of its own, as though it had acquired the capacity to function independently of the agency that initially set it in place.

Invested with corrosive desire, arrested by inequality, and battered by the shattering reality of escalating global turmoil, humanity carries on playing with the Devil, inexorably dependent on nature, bewitched by material culture whilst thoroughly subjected to a perverse political endgame.

Text: Bernardo José de Souza

read less